There’s no telling when or why a memory returns, or you could say, arrives like a dream. Today my mind goes way back to 1977, the summer before I started college. My friend Todd Parker, from the cross country team, has finished his Freshman year at Oregon State University, where he studies Forestry Science. This summer he’s marooned at a remote fire watch tower in Western Oregon. A group of us, all fellow cross country veterans, make the trip to visit him out in the deep woods, driving for hours over rutted dirt roads under a vast canopy of trees.

I know John Rockwood is there because we drove in his sixties-era, bamboo-yellow Studebaker, inherited from his grandmother. Who else is there? Jim Crawford, Steve Mandella or Kelly Eckart may have been the others on the trip. We could have easily fit five of us in the Studebaker, as we did so many times on summer training runs. It’s a cloudy day, no surprise, and it feels like we’re driving underwater in a grey-green sea. We finally catch sight of the tower with its long stilted legs and tiny shack atop, where Parker has been living alone for several months. When we get close, Parker shouts down and waves to us from the flat top of the tower; he leans out precariously over the edge. By the time we stop the car, he’s already descending a narrow ladder. He jumps off several rungs from the bottom. He wants to walk with us on the trails around the tower. Perhaps a little crazed from his isolation and not sure how to act at first, Parker mumbles to himself and laughs nervously. As we walk along, he recites the Latin scientific classifications for the surrounding trees and undergrowth. He points to the giant Douglas Firs overshadowing us: “Pseudotsuga menziesii” and to the bracken and sword ferns which cover the ground: “Pteridium aquilinum” and “Polystichum minimum,” respectively. We ask about a shrub with reddish-orange berries. “Salmonberry,” he says, “but more precisely, Rubus spectabilis.” Of course I can’t remember these Latin names and have to look them up, but I do remember Parker claims the ferns and berries are edible and he has tried them all. “The berries are okay but the ferns taste like shit,” he says. Parker rarely passes up a perfectly legitimate opportunity to cuss.

After our walk in the woods, Parker takes us for a tour of his station. Near the tower, there’s an outhouse and a small shed with shovels, rakes, a backpack pump, protective gloves and goggles, a headlamp, some basic hand tools, and lot of detritus I can’t identify. Up in the tower, everything is in a single room with windows on all sides. There’s a small kitchen setup with basic cookware and utensils, canned pears, chili, corn and green beans, Campbell’s soup (a lot), a canister of rice, a bag of potatoes, several large plastic water containers—but no running water of any kind. Parker proudly holds up his plastic pee pot, half full, and tells us, “There’s no way I’m going down that ladder to the outhouse in the dead of night.” In one corner a sleeping cot, unmade; in another corner, bookshelves lined with instruction manuals, log books, and a hammered copy of Tolkien’s Fellowship of the Ring. In the center of the room, a table with a big ham radio, topographic maps, and a pair of fancy binoculars. Most conspicuous of all are two telescopes on swiveling stands that allow Parker to see the horizon in any direction. No stereo or TV, of course, nothing to distract him from his singular task: looking out for any sign of smoke. We each have a look through the telescopes: nothing but dark green, swaying treetops and grey skies. It’s like being lost at sea.

At one point we all go up to the roof of the tower where Parker has a 360-degree view of the surrounding forest. This is the moment I remember most of all. The haunting quiet: only the wind moving through endless pines like the sound of distant ocean surf. I can feel the forest and sky cooly watching us. It’s a flat metal roof with no railings. Parker—accustomed to his perch at these heights—walks out to the very edge of the roof, even putting his toes over the rim and leaning out. Parker may be showing off a bit. I don’t think I ever experienced such intense vertigo before or since. It is all I can do to keep from shouting at him: “Get back!” The rest of us stay close to the center of the roof and the ladder back down into the shelter. Being up there at all is more than enough.

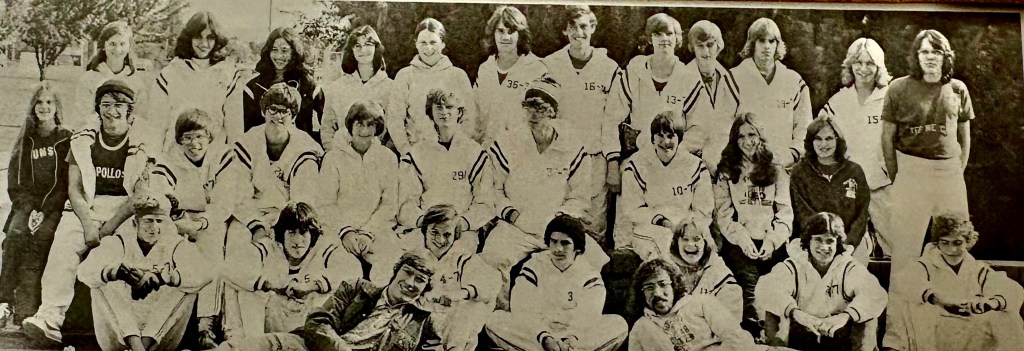

Why this memory comes back today, I’m not sure, but now that it has come back, I’m missing these old friends I haven’t seen in decades—the whole cross country team, both young men and women and coaches, often calling each other by our last names: Robbins, Daniels, Wierson, Forbes, Chadwick, Parker, Rockwood, Mandella, Eckart, Ballas, Arthur, Boone, Clymore, Cooper, Kainz, Swartzfager, Crawford, Lenzer, Weidkamp, Gregor, Vincent, Riechers, Von Weller, Focht, Carlile, Schaller, McInnis, Weston, Cantwell. The names familiar still, after so many years.

We were a motley crew, a ragtag platoon—sharing something akin to combat camaraderie. Thousands of running miles on roads and trails. The grueling summer training, early morning runs, and daily workouts after school that pushed us to exhaustion. The nerves, pain, high emotion, and exhilaration of the races—the meets—bus rides all around town in Portland, races both lost and won, injuries, miracles and out-of-our-minds sprints to the finish. Though many of us have long ago lost track or even forgotten each other, it’s all in there somewhere, in our combined memories. It happened. So it will always be happening.